data_dir = "https://datasci112.stanford.edu/data/"

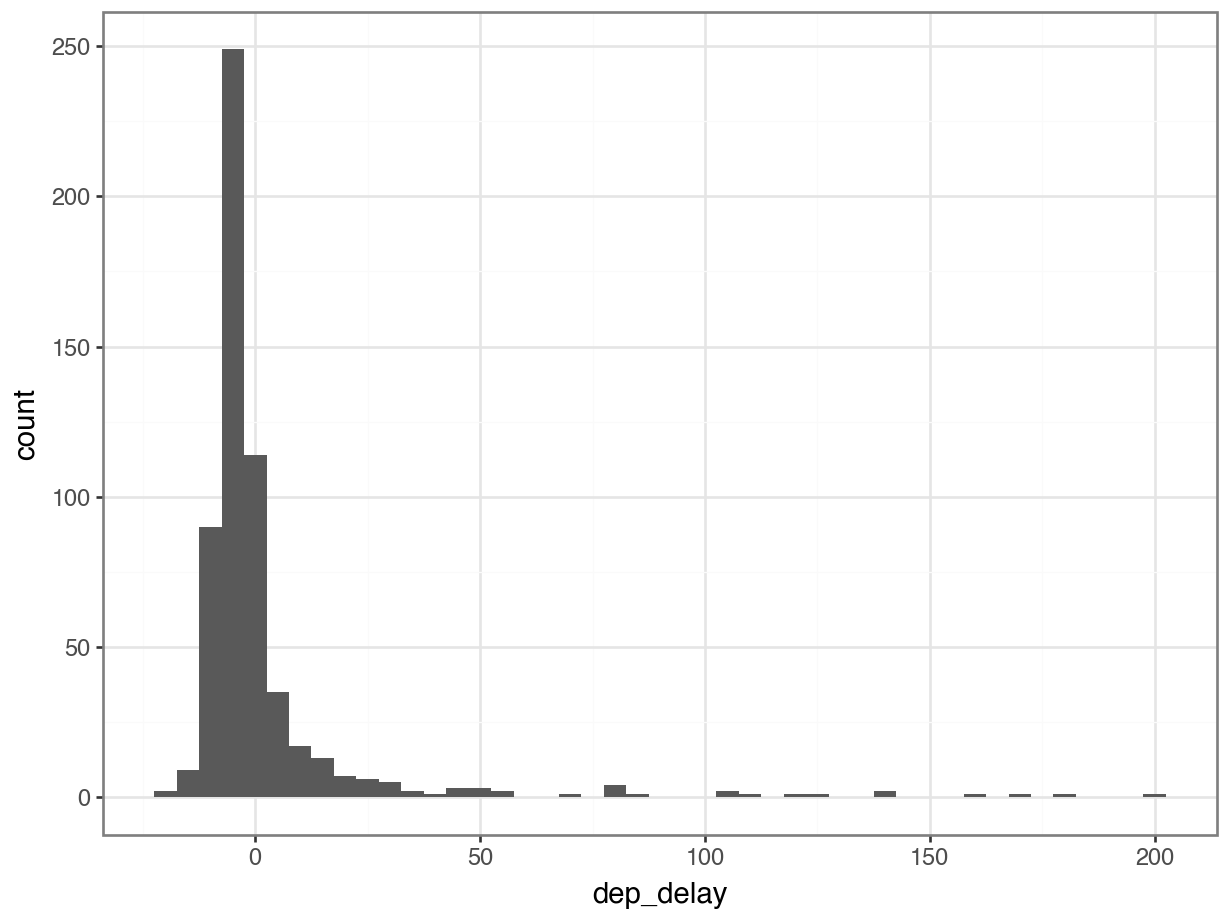

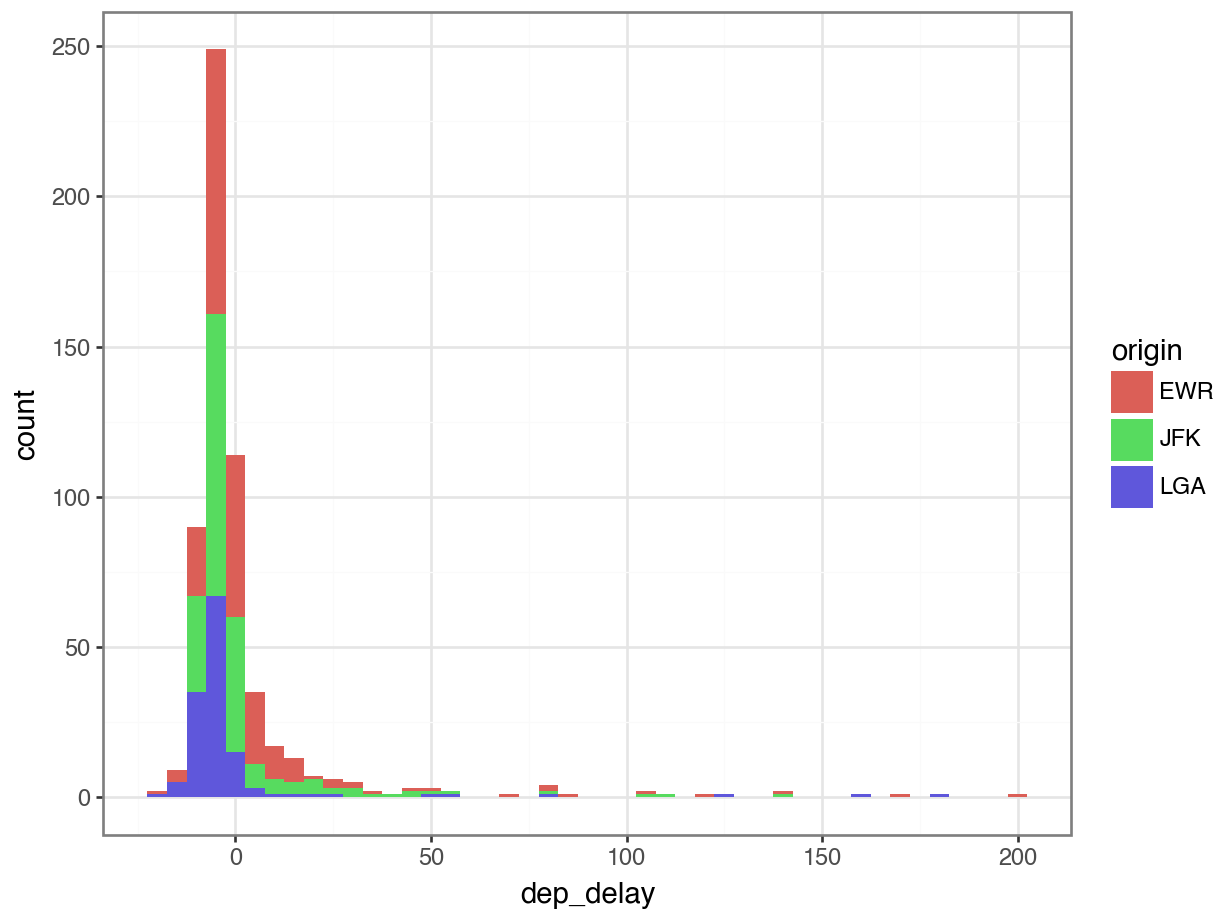

df = pd.read_csv(data_dir + "flights_nyc_20131116.csv")

df carrier flight origin dest dep_delay

0 US 1895 EWR CLT -5.0

1 UA 1014 LGA IAH -3.0

2 AA 2243 JFK MIA 2.0

3 UA 303 JFK SFO -8.0

4 US 795 LGA PHL -8.0

.. ... ... ... ... ...

573 B6 745 JFK PSE -3.0

574 B6 839 JFK BQN 0.0

575 UA 360 EWR PBI NaN

576 US 1946 EWR CLT NaN

577 US 2142 LGA BOS NaN

[578 rows x 5 columns]