titanic = pd.read_csv("data/titanic.csv")

titanic["Pclass"] = titanic["Pclass"].astype("category")

titanic["Survived"] = titanic["Survived"].astype("category")Visualizing and Summarizing Quantitative Variables

Some Class Updates!

Changes from Week 1

Week 1 taught me that I need to make some adjustments!

Lab Attendance

Is not required. However, if you do not attend lab and come to student hours or post questions on Discord about the lab, I will be displeased.

Deadlines

Labs will be due the day after lab.

- Tuesday’s lab is due on Wednesday at 11:59pm.

- Thursday’s lab is due on Friday at 11:59pm.

Quizzes from the lecture slides are due by 11:59pm that night.

Lab Activities

I’m going to do my best to ensure all the skills necessary to complete the lab activities are covered during lecture.

The story so far…

Getting, prepping, and summarizing data

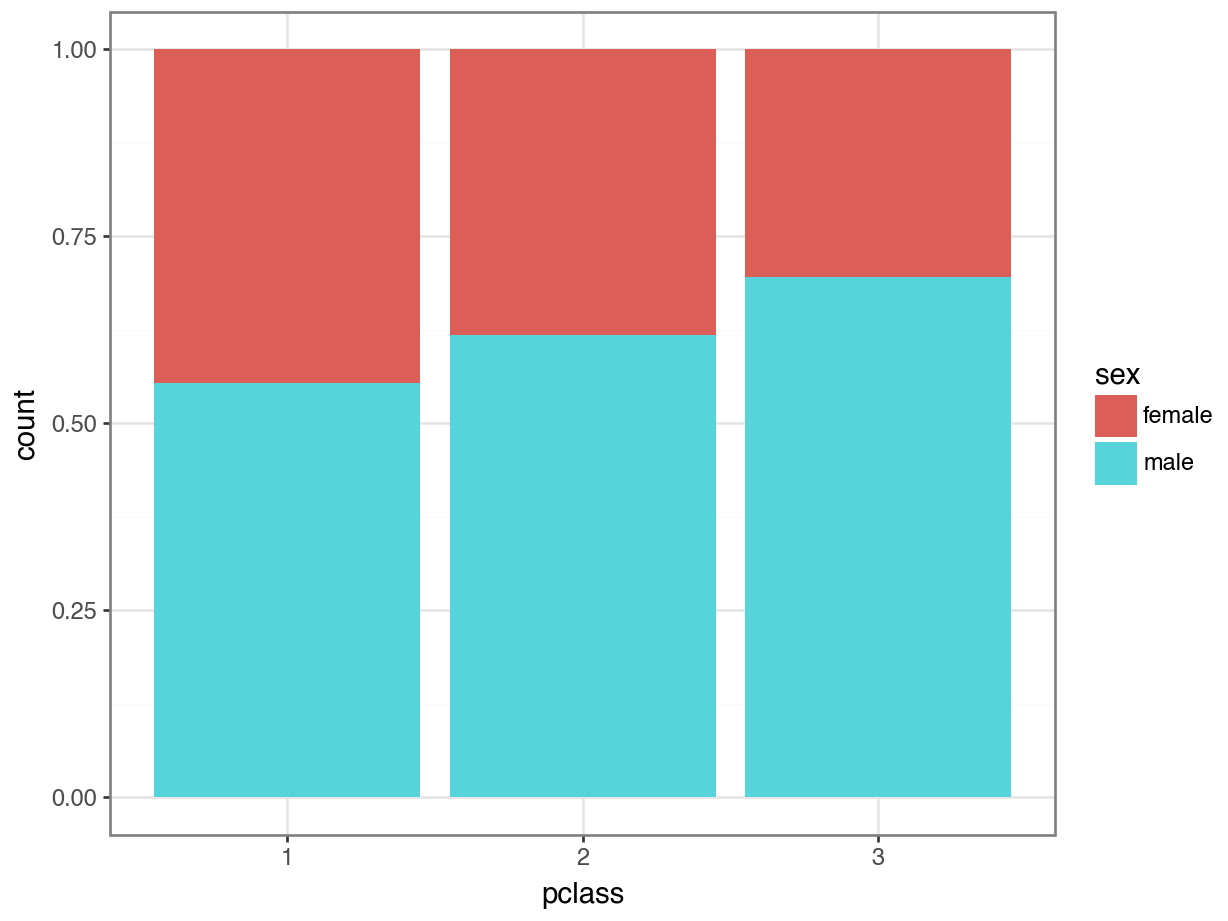

Marginal Distributions

If I choose a passenger at random, what is the probability they rode in 1st class?

Joint Distributions

If I choose a passenger at random, what is the probability they are a woman who rode in first class?

Conditional Distributions

If I choose a woman at random, what is the probability they rode in first class?

Visualizing with plotnine

Quantitative Variables

We have already analyzed a quantitative variable in the COVID data!

Visualizing One Quantitative Variable

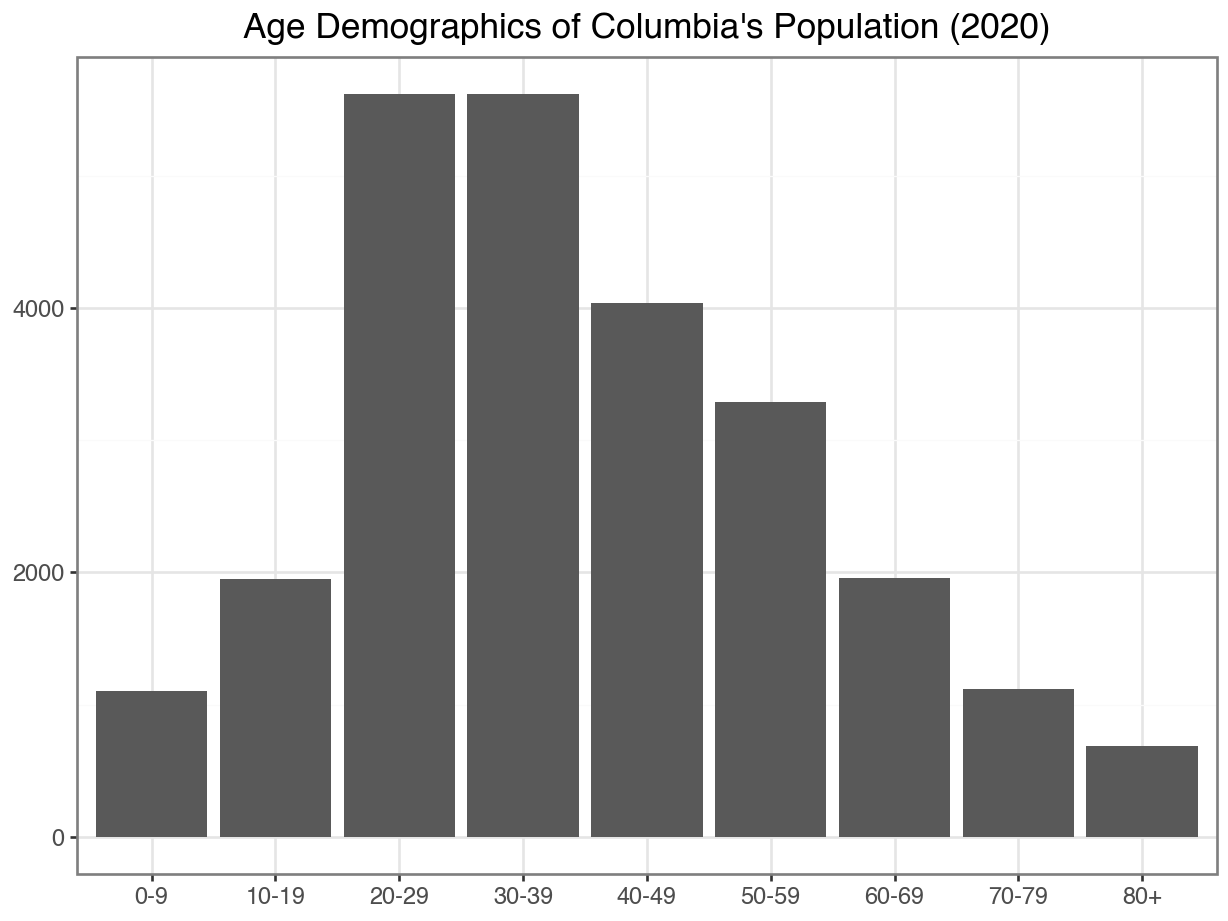

Option 1: Convert it to categorical

To visualize the age variable, we did the following:

Option 1: Then make a barplot

Then, we could treat age as categorical and make a barplot:

But this process seems a bit odd…

Option 2: Treat it as a quantitative variable!

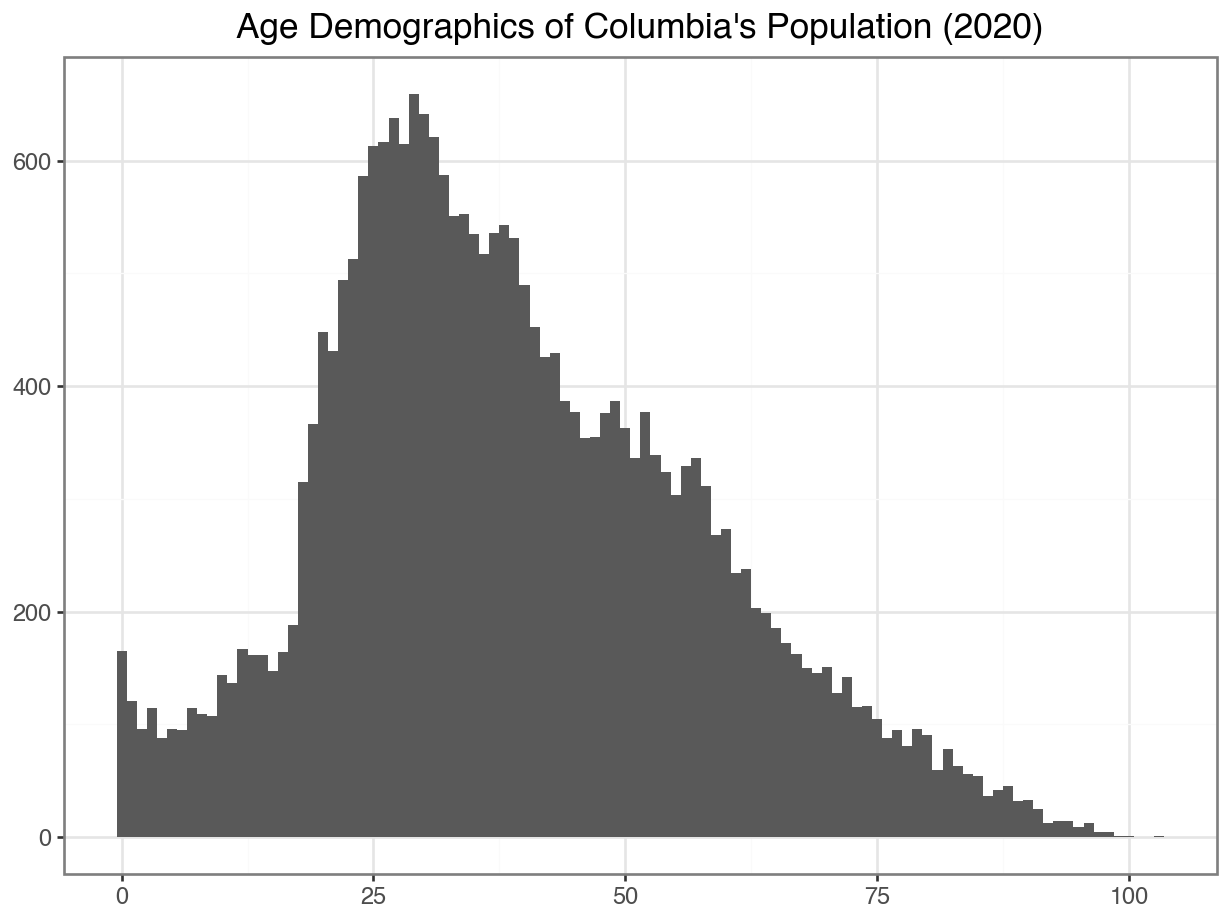

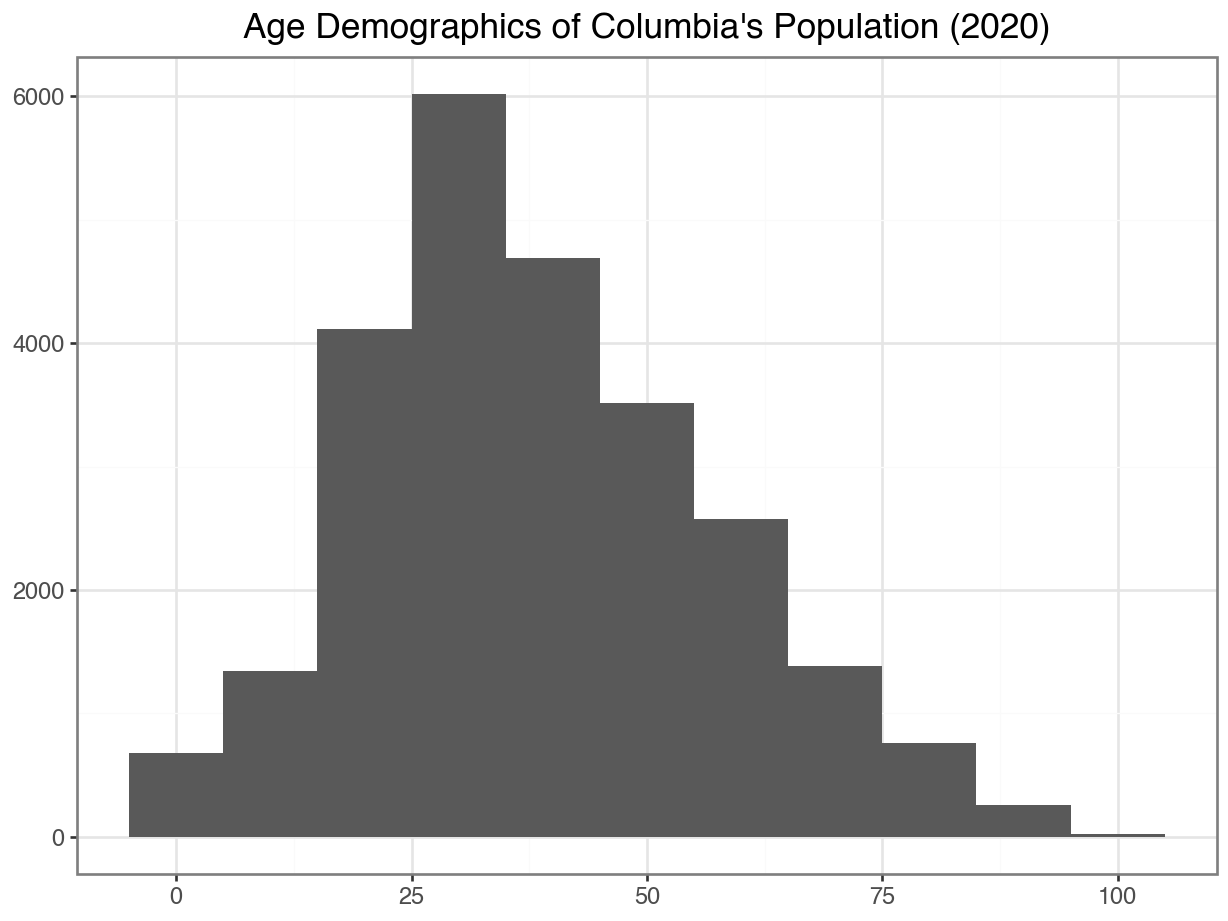

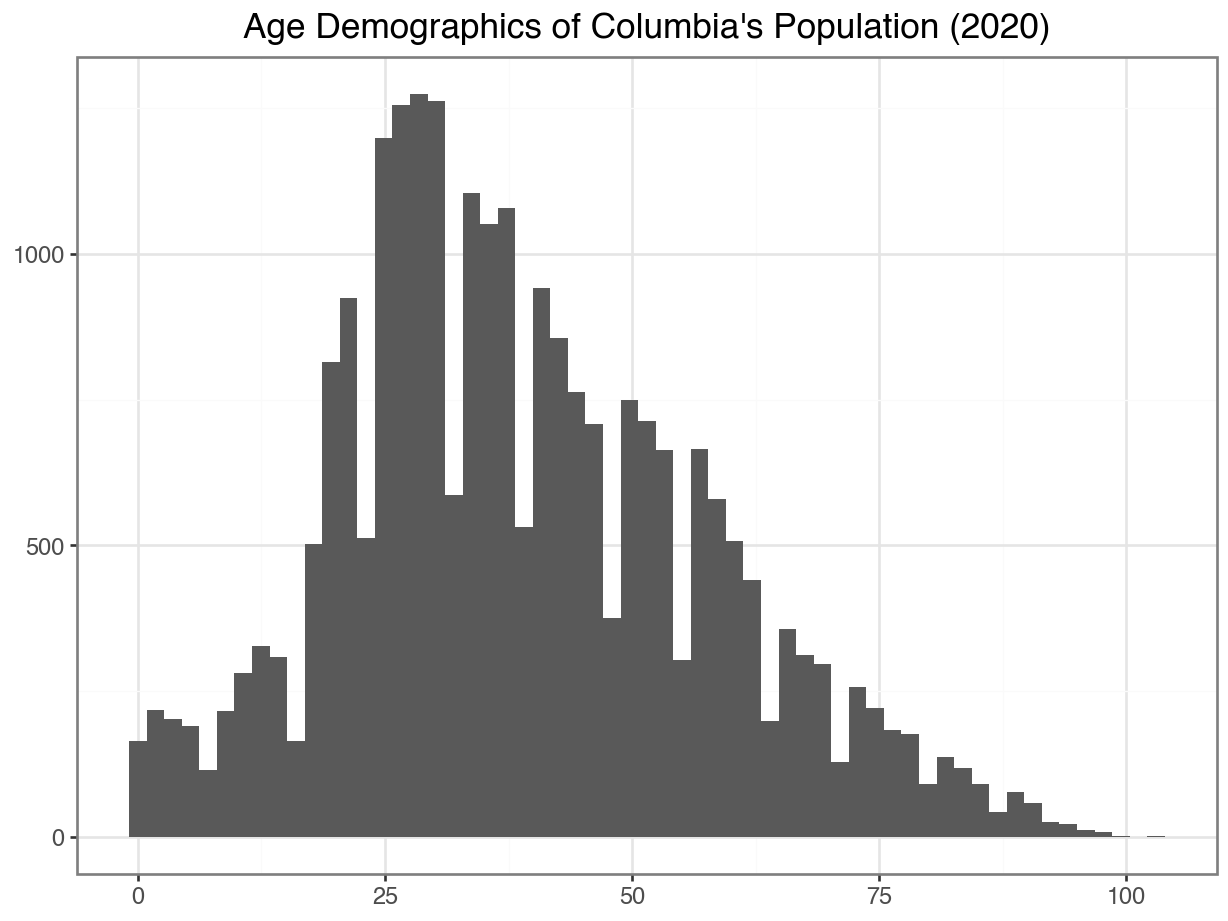

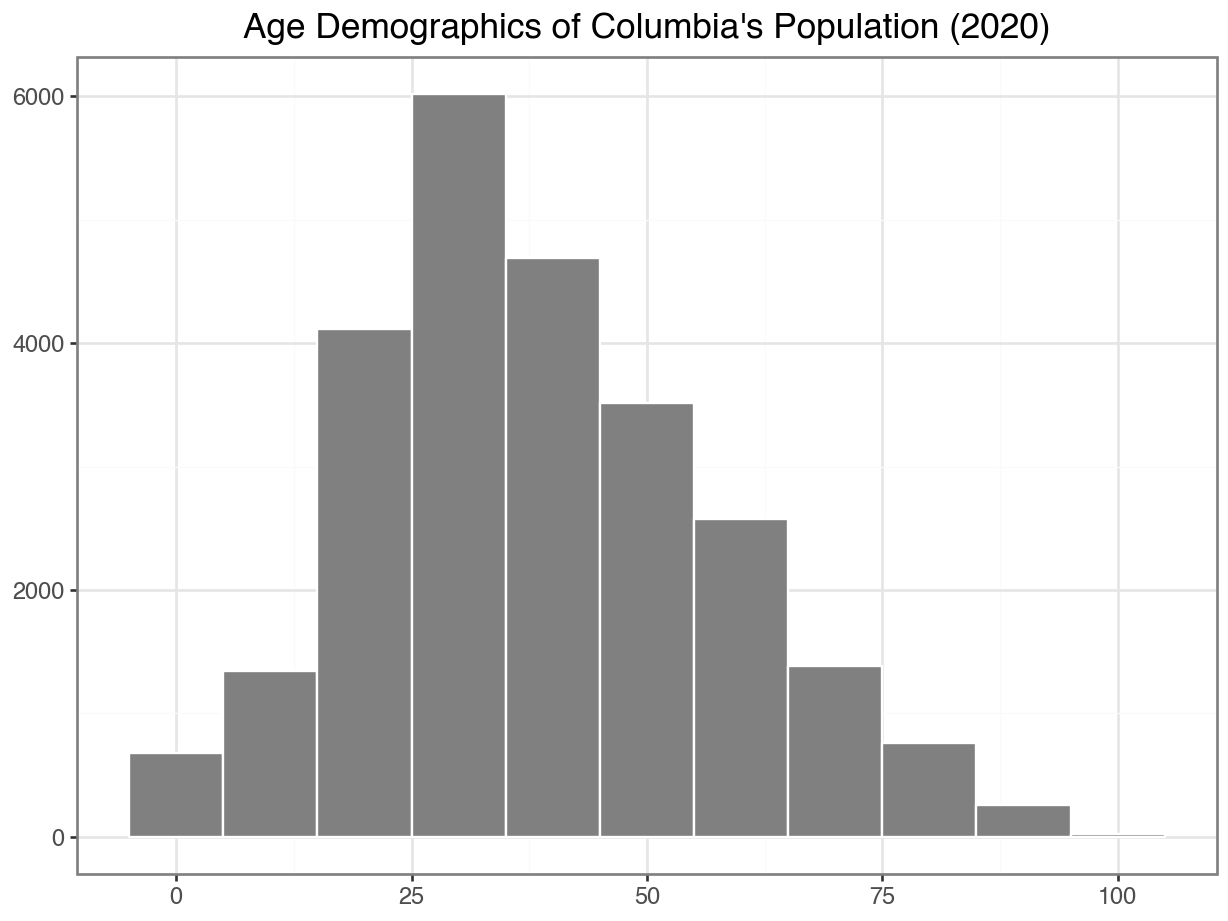

A histogram uses equal sized bins to summarize a quantitative variable.

Adding Style to Your Histogram

Changing Binwidth

To tweak your histogram, you can change the binwith:

Adding Color & Outline

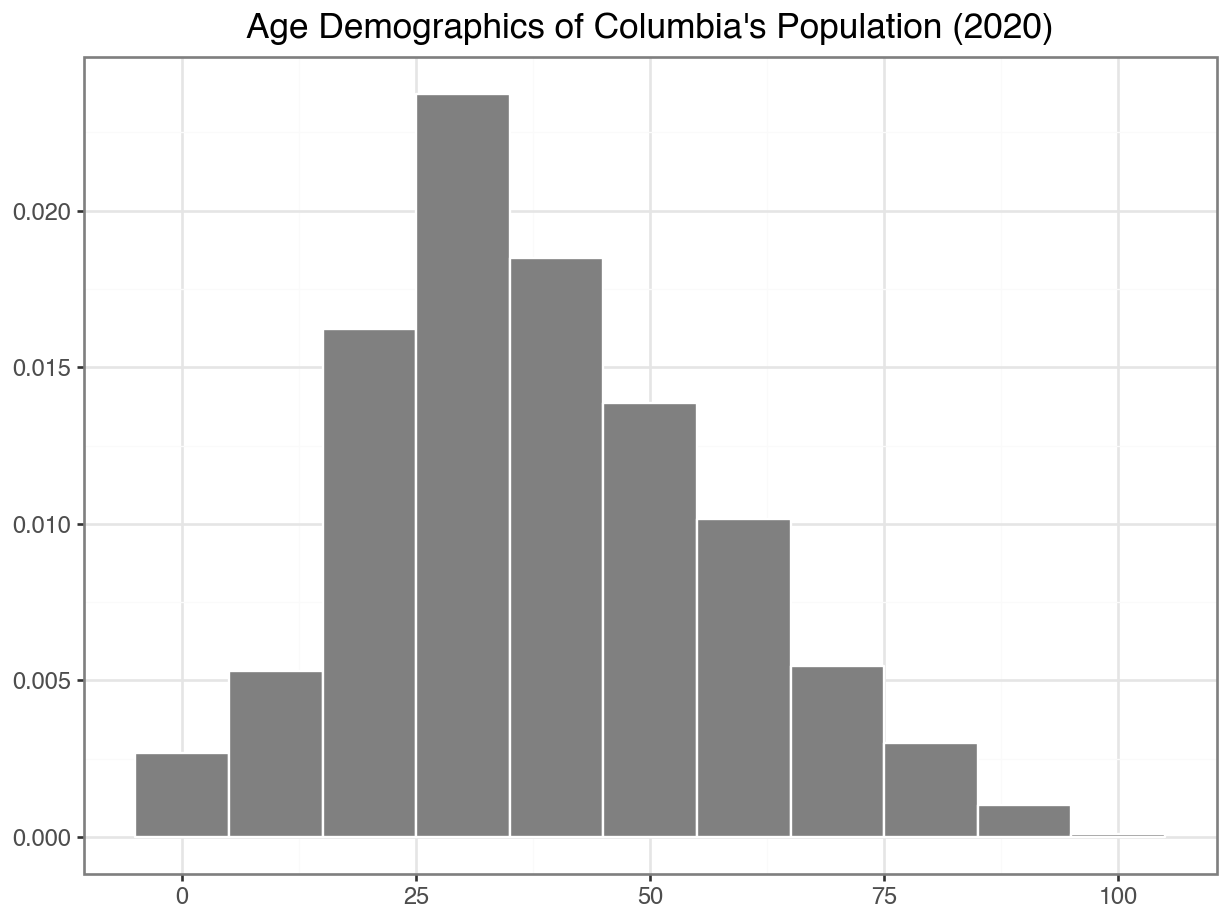

Using Percents Instead of Counts

Distributions

Recall the distribution of a categorical variable:

- What are the possible values and how common is each?

The distribution of a quantitative variable is similar:

- The total area in the histogram is 1.0 (or 100%).

Densities

In this example, we have a limited set of possible values for

age: 0, 1, 2, …., 100.- We call this a discrete variable.

What if had a quantitative variable with infinite values?

- For example: Price of a ticket on Titanic.

- We call this a continuous variable.

- In this case, it is not possible to list all possible values and how likely each one is.

- One person paid $2.35

- Two people paid $12.50

- One person paid $34.98

- \(\vdots\)

- Instead, we talk about ranges of values.

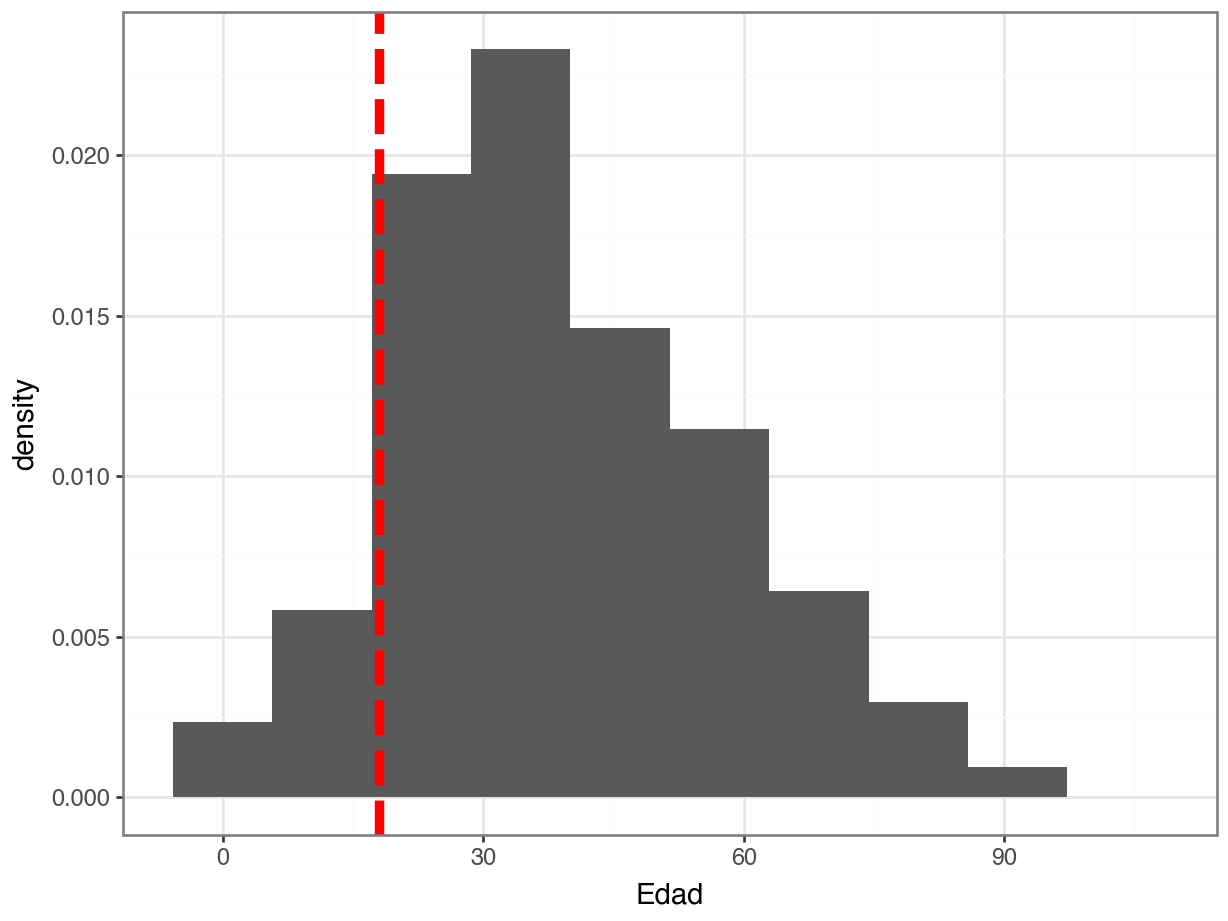

Densities

About what percent of people in this dataset are below 18?

How would you code it?

Summarizing One Quantitative Variable

Summaries of Center: Mean

Mean

One summary of the center of a quantitative variable is the mean.

When you hear “The average age is…” or the “The average income is…”, this probably refers to the mean.

Suppose we have five people, ages:

4, 84, 12, 27, 7The mean age is: \[(4 + 84 + 12 + 27 + 7) / 5 = 134 / 5 = 26.8\]

Notation Interlude

To refer to our data without having to list all the numbers, we use \(x_1, x_2, ..., x_n\)

In the previous example, \(x_1 = 4, x_2 = 84, x_3 = 12, x_4 = 27, x_5 = 7\). So, \(n = 5\).

To add up all the numbers, we use the summation notation: \[ \sum_{i = 1}^5 x_i = 134\]

Therefore, the mean is: \[\bar{x} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^n x_i\]

Means in Python

Long version: find the sum and the number of observations

Activity 2.1

The mean is only one option for summarizing the center of a quantitative variable. It isn’t perfect!

Let’s investigate this.

Open the Activity 2.1 Collab notebook

Read in the Titanic data

Plot the density of ticket prices on titanic

Calculate the mean price

See how many people paid more than mean price

What happened

Our

faredata was skewed right: Most values were small, but a few values were very large.These large values “pull” the mean up; just how the value

84pulled the average age up in our previous example.So, why do we like the mean?

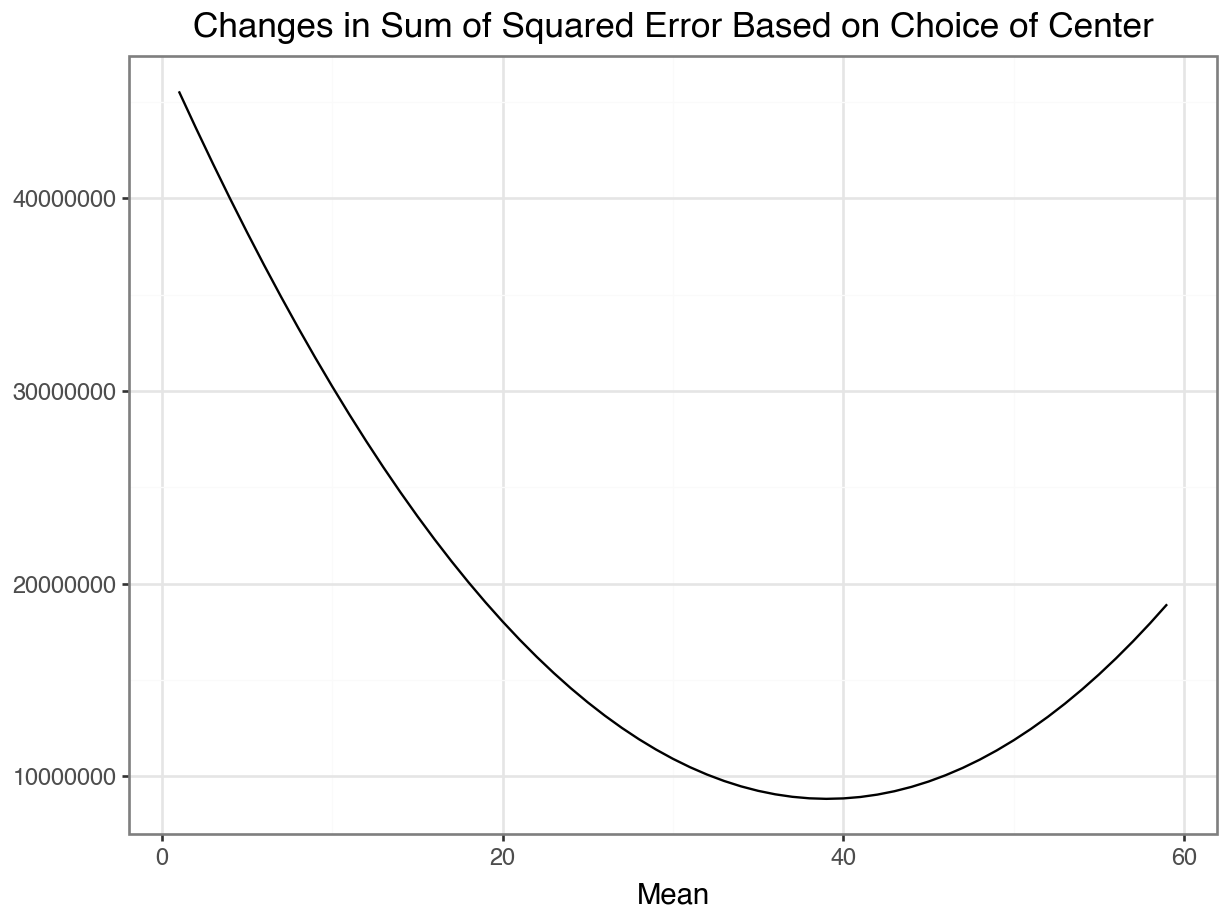

Squared Error

- Recall: Ages 4, 84, 12, 27, 7.

- Imagine that we had to “guess” the age of the next person.

Minimizing squared error

Code

cs = range(1, 60)

sum_squared_distances = []

for c in cs:

(

sum_squared_distances

.append(

(

(df_CO["Edad"] - c) ** 2

)

.sum()

)

res_df = pd.DataFrame({"center": cs, "sq_error": sum_squared_distances})

(

ggplot(res_df, aes(x = 'center', y = 'sq_error')) +

geom_line() +

labs(x = "Mean",

y = "",

title = "Changes in Sum of Squared Error Based on Choice of Center") +

theme_bw()

)

Summaries of Center: Median

Median

Another summary of center is the median, which is the “middle” of the sorted values.

To calculate the median of a quantitative variable with values \(x_1, x_2, x_3, ..., x_n\), we do the following steps:

Sort the values from smallest to largest: \[x_{(1)}, x_{(2)}, x_{(3)}, ..., x_{(n)}.\]

The “middle” value depends on whether we have an odd or an even number of observations.

If \(n\) is odd, then the middle value is \(x_{(\frac{n + 1}{2})}\).

If \(n\) is even, then there are two middle values, \(x_{(\frac{n}{2})}\) and \(x_{(\frac{n}{2} + 1)}\).

Note

It is conventional to report the mean of the two values (but you can actually pick any value between them)!

Median in Python

Ages: 4, 84, 12, 7, 27. What is the median?

Median age in the Columbia data:

Summaries of Spread: Variance

Variance

One measure of spread is the variance.

The variance of a variable whose values are \(x_1, x_2, x_3, ..., x_n\) is calculated using the formula \[\textrm{var(X)} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n - 1}\]

Does this look familiar?

It’s the sum of squared error! Well, divided by \(n-1\), the “degrees of freedom”.

Variance in Python

Similar to calculating the mean, we could find the variance manually:

np.float64(348.0870469898451)Standard Deviation

Notice that the variance isn’t very intuitive. What do we mean by “The spread is 348”?

This is because it is the squared error!

Takeaways

Takeaway Messages

Visualize quantitative variables with histograms or densities.

Summarize the center of a quantitative variable with mean or median.

Describe the shape of a quantitative variable with skew.

Summarize the spread of a quantitative variable with the variance or the standard deviation.